Interval timing and temporal learning

Many factors influence how individual organisms learn the time between one recurring event and another. We are investigating the significance of different initiating events, rates of change in dynamic environments, and the role of environmental context on temporal learning and adaptation. Different metrics have been developed to characterize temporal discrimination. We are exploring and comparing them in work on:

Cue informativeness - Sometimes, different stimuli signal different outcomes with certainty - they are informative cues (e.g., where the wheel lands in The Price Is Right signals how much money the contestant wins). Sometimes different stimuli signal the same outcome - uninformative cues (e.g., every color of Skittles is the same flavor). Sometimes, cues are partially informative (e.g., a poker player has a 'tell' that she uses to her advantage when bluffing). We evaluate and model how learning about cues interacts and competes with learning about outcomes to enable individuals to predict when future events will occur.

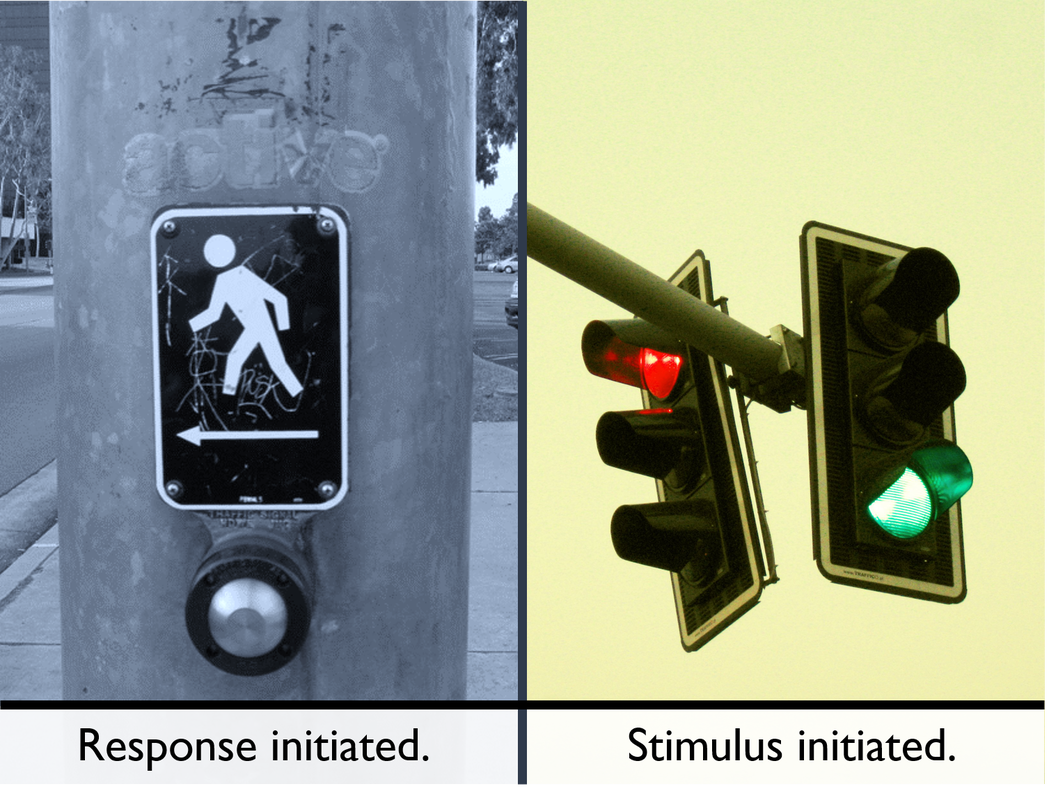

Response initiation requirements - Some properties of responding in interval schedules are very different when the event that initiates the interval is generated by the animal itself, rather than produced independently of the animal’s behavior. Other properties are essentially identical. We are characterizing differences between subject- and computer-initiated intervals in order to explain the mechanism driving those differences.

Temporal discrimination dynamics - Temporal control can adjust rapidly when intervals change frequently. We are conducting experiments designed to identify the ways in which direct and contextual information contribute to temporal discrimination in dynamic environments

Temporal bisection - What determines whether an interval is judged short or long?

Cue informativeness - Sometimes, different stimuli signal different outcomes with certainty - they are informative cues (e.g., where the wheel lands in The Price Is Right signals how much money the contestant wins). Sometimes different stimuli signal the same outcome - uninformative cues (e.g., every color of Skittles is the same flavor). Sometimes, cues are partially informative (e.g., a poker player has a 'tell' that she uses to her advantage when bluffing). We evaluate and model how learning about cues interacts and competes with learning about outcomes to enable individuals to predict when future events will occur.

Response initiation requirements - Some properties of responding in interval schedules are very different when the event that initiates the interval is generated by the animal itself, rather than produced independently of the animal’s behavior. Other properties are essentially identical. We are characterizing differences between subject- and computer-initiated intervals in order to explain the mechanism driving those differences.

Temporal discrimination dynamics - Temporal control can adjust rapidly when intervals change frequently. We are conducting experiments designed to identify the ways in which direct and contextual information contribute to temporal discrimination in dynamic environments

Temporal bisection - What determines whether an interval is judged short or long?

Timing in response-initiated fixed intervals.

Fox, A. E. and Kyonka, E. G. E. (2015), Timing in response-initiated fixed intervals. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 103, 375-392. doi: 10.1002/jeab.120

|

Time markers are events that predict when other events will occur. Sometimes time markers are events generated by the subject (i.e., responses), such as pressing a button at a crosswalk. Other time markers are events that aren’t under the subject’s control, like most traffic lights.

We investigated whether the type of time marker would affect temporal discrimination: Pigeons were exposed to fixed-interval schedules in which the onset of the interval was signaled by the illumination of a key light or initiated by a peck to a lighted key. Food was delivered following the first response after the interval elapsed. In Experiment 2, on occasional trials food was not delivered (i.e. “no-food” or “peak trials”). |

A yoking procedure equated reinforcement rates between the schedule types in both experiments. Absolute response rates early in the intervals were higher in the response-initiated schedules, but patterns of responding between interval onset and food delivery were similar for intervals initiated by responses and stimulus changes. However, during peak trials in Experiment 2 the duration of responding at a high rate was longer for response-initiated schedules than stimulus-initiated schedules. This suggests that timing precision was reduced in the response-initiated schedules and that relative “distinctiveness” of a time marker may determine its efficacy.