Interval Timing

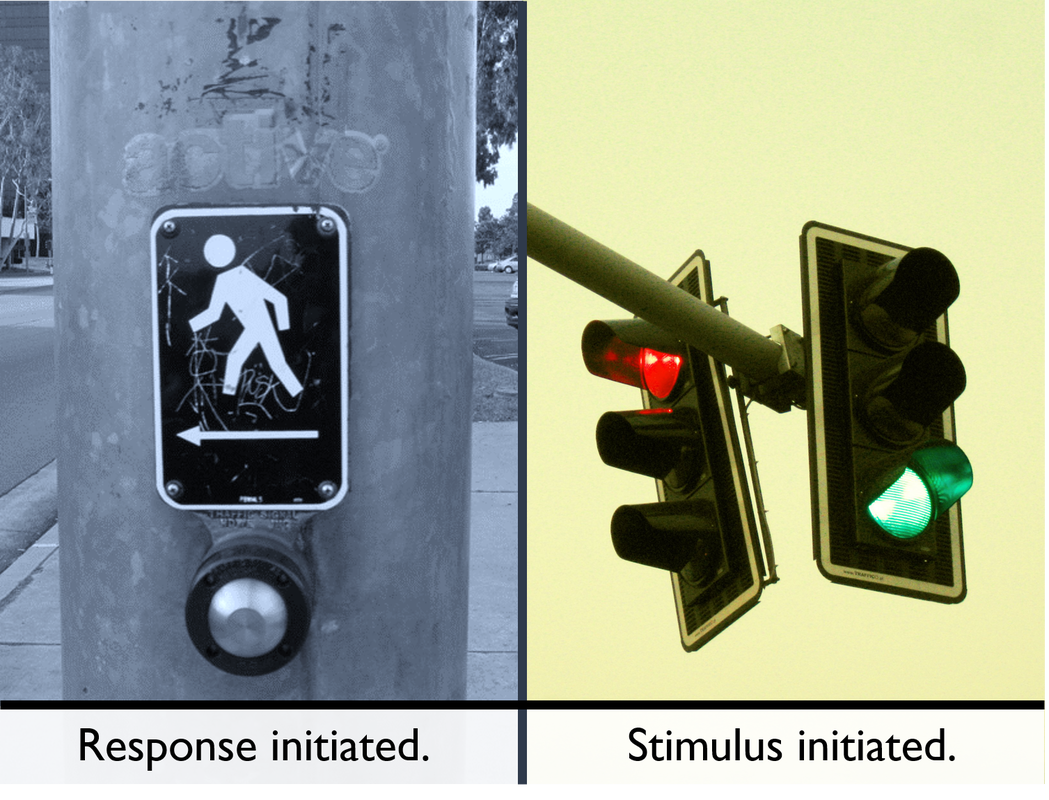

All recurring events occur on some schedule. Using schedules of reinforcement in relatively simplified and constrained laboratory conditions makes it possible to separate signal from noise and evaluate behavior-environment relations. Here is some of our work using schedules of reinforcement to study interval timing.